- Molly O’Callaghan, a 19-year-old swimmer from Australia, etched her name in the annals of swimming history with a remarkable performance in the Women’s 200m Freestyle event

- Akshay Bhatia, 21, Wins his First PGA Tour Title at the Barracuda Championship

- Bruno Fernandes Replaces Harry Maguire as New Man Utd Captain

- Lionel Messi Surprises Teammate in group chat ahead of Grand Unveiling

- Man Utd Sign Keeper Andre Onana from Inter

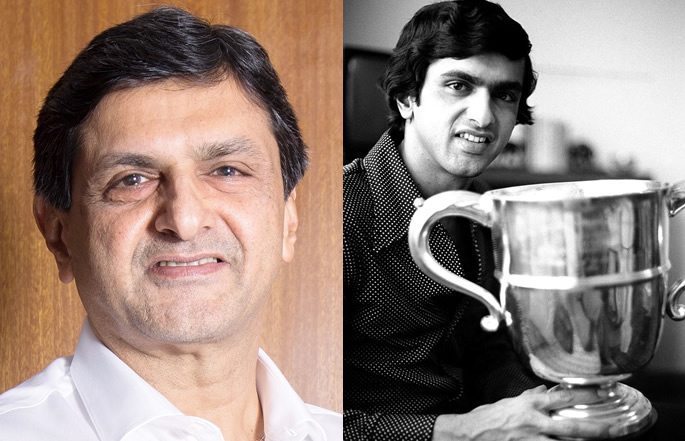

Prakash Padukone – humble champion who changed the face of sport forever

- Updated: April 20, 2020

- 1993

There comes the odd, rare occasion when a journalist stares blankly at either his writing pad or his computer screen, and wonders how to tackle the subject at hand. Not because of a shortage of background data, but because of a huge surfeit of material at hand. As also a close personal connect.

It is this maelstrom of emotions that invades my psyche as I sit down to write the final profile in this series, on the living legend that is Prakash Padukone. How do I present an iconic player who was my hero, even though he was five years my junior, and not easily accessible, as he lived in Bangalore (and later, for six years, in Denmark), while I was firmly a Bombaywalla (or the more politically correct ‘Mumbaikar’).

As fellow exponents of the shuttle sport, we both played in tournaments all over the country, but quality-wise, it was like a Beauty-and-the-Beast comparison. Prakash was already firmly in the badminton stratosphere, which I could never hope to reach. On the few occasions that we clashed against each other in tournaments, he would swat me aside as one would an irritating insect, albeit with finesse and an apologetic look.

We shared a very special bond – I was at courtside in the Wembley Arena in my capacity as a photo-journalist when, on 23 March, 1980, Padukone dealt with the two-time defending champion, Liem Swie King, in the same manner as he dealt with all-comers in India at the time.

A scoreline of 15-3, 15-10 in the final of All England Championship, until then considered the unofficial world championship, provided mute testimony of the dizzy heights he reached that day.

As I have written elsewhere, I still have in my possession, sealed in a plastic bag, the T-shirt in which he won that title. He had smilingly handed it over to me in the changing room after the match, in response to my heartfelt entreaty for an item of his playing attire to commemorate his epochal victory.

That All England crown though isn’t the only crowning glory of his illustrious career. In fact, it marked the clean sweep of the European titles that year – bagging the Danish, Swedish and English crowns. He reached the All-England final the following year to, but was beaten by the man whom he had deprived of a hat-trick of All-England crowns in 1980.

Prakash’s other international titles include a Commonwealth Games gold medal in 1978. He went on to win the inaugural World Cup in Kuala Lumpur in 1981 at the expense of China’s Han Jian in the final, by a 15-0 (yes, a love-game in an international final), 18-16 scoreline. In addition, he was a bronze medallist at the 1983 World Championships held in Copenhagen.

Prakash won the men’s and junior boys’ national titles as a 16-year-old in the 1971-72 Indian Nationals, and was also runner-up in the boys’ doubles. He went on to win nine National singles titles in an unbroken reel until 1979-80, in addition to five men’s doubles titles. However, he was beaten in the singles final of the 1980-81 Nationals in Vijayawada by Syed Modi. Several more attempts to obtain that elusive tenth National title were to end in failure.

How Prakash got into badminton is a piquant story in itself. Born in Bangalore on 10 June 1955, he started playing at the age of seven, in 1962, at a time when badminton was not popular in the southern part of India. It was played mainly in the North, West, and East.

“There was another sport called ball badminton that was played in the South with a yellow woollen ball, with five players on each side,” he reminisces. “So nobody knew anything about badminton. You had to specify shuttle badminton; otherwise, saying just badminton meant ball badminton. That was how popular badminton was in the South during the 1960s. So you have to realise the context within which I started playing.”

One of the first lessons he learned about playing badminton was from his father. “My father’s advice to me when I was very young was – focus on things under your control. This is all you will get; don’t ask for anything more. Don’t say, ‘If I had a Chinese coach, a Japanese racket and European infrastructure…’ You will not get any of it; yet you have to be the best in the world.”

Prakash’s father was the state administrator for shuttle badminton, and the first to form the state association called Mysore, before Karnataka came in. “He was the association’s first coach, and he was also my first coach,” he says. “He taught me and some of my friends in a small club that was basically a marriage hall. It used to be booked for marriages six months in the year.

“So when there was no wedding, then we could go and play there. The choice was – either you do that, or there was nothing else! There was no third option. I started playing, not with the intention of becoming a champion. My father used to go and play just for fitness. He used to come back late from work – at around 6 pm, and then we kids would go with him to play.”

One of the advantages of shuttle badminton was that, being an indoor sport, players could continue playing even when it got dark outside for outdoor sports.

“There were some other state players playing in the hall, and I just picked up the game by watching them and trying the shots they played,” he reminisces. “At the time, I had absolutely no idea that I would go on to play for the country. I just played for the enjoyment of the sport; there were no goals, no aims, no ambitions.”

It was much later – at the age of 16, when the school-going kid won the junior and senior singles titles at the same Nationals in Madras that he realised that he had that little something extra; and, if he put in the effort, he could aspire to play professionally, and making a mark at the national and international level.

Prakash heralded his arrival on the big stage by annexing the men’s singles, pipping Punjab’s Devinder Ahuja 18-17 in the decider. When he next met Ahuja in a National final, in 1975-76 at Goa, the scores were a 15-6, 15-0 rout, and the stylish strokemaker from Amritsar was reduced to the status of a spectator.

Always a stickler for hard work, Prakash placed great emphasis on training, and was fortunate to have three other badminton players in his neighbourhood who were equally dedicated – Kiran Kaushik, PG Chengappa and Narendra Ubhayakar. On most pre-dawn mornings, the four could be seen racing down the road towards the park where they would do various exercises to improve their speed and endurance.

In fact, there was a period when Prakash was unbeaten at the domestic level for a three-year span – a period that came to an end when he suffered defeat at the hands of stonewaller Iqbal Maindargi at the CCI courts in Bombay, at 13-15 in the decider in 1977. It was a privilege for me to do the television commentary on the match for Doordarshan.

Prakash’s epochal All-England title triumph in 1980 changed things for him, and for Indian badminton, forever.

“When we talk of Indian history, we talk of 1947 as the mark around which history revolved – pre-Independence and post-Independence,” says Prakash. “For Indian badminton, that date was probably 1980, when I won the All-England. That was the hallmark.

“Before 1980, badminton was popular and was being played in the country, but I would call it a minority sport, like any other, where there was not much media coverage, not much money, only the players who played and their parents knew what badminton was. There were not many facilities, there was not much international exposure.

“Post-1980, all that changed. Badminton became a major sport – to be counted among the top five sports in India, in the same bracket as cricket, hockey, football and tennis. People started following badminton, since I had started doing well. I think, any sport requires one player to be at the top; and that sport automatically starts getting more coverage because people start following it. Then it is up to the government and the federations to take it to the next level, to make it more popular.”

And how did the Denmark contract come about? Did the 1980 All-England triumph hasten its signing? “Coming from a middle-class family, I already had a good job with a government-owned bank,” Prakash reminisces. “When I won the Commonwealth Games gold in 1978, I got a promotion. In 1980, when I won the All-England, I got another promotion. So I was quite senior in the bank.

“My parents, coming from a traditional family, told me that I had such a good secure government job, I could do very well and rise in the bank. Initially, Denmark was a one-year contract, so my parents asked me what I would do if the contract was not renewed. I said I had to take a chance, if I wanted to remain on the top. In India, badminton was still in its nascent stages; and, after I reached a certain stage, I needed to move out, because there were not enough facilities or quality players to practice against, as there are in the academies now.”

At the time, there were no sports management agencies; and half of Prakash’s time would be spent travelling to Delhi to make travel arrangements, get visas, etc. It had become far too tiresome and time-consuming.

“Before the All-England win, I had already hired a full-time manager, and paid him out of my earnings,” says Prakash. “He got me a contract to move to Denmark, and I eventually stayed there for six years – something that my parents were not at all in favour of. My point was, I had already won nine national titles by 1980, when I secured my Denmark contract.

“I was not keen to come back to India immediately, but my parents insisted that I return and get the tenth title, and then leave. But I was beaten in the 1980-81 final in Vijayawada by Syed Modi, who was an up-and-coming player at the time.”

Not generally one to give excuses, Prakash feels that when he reached Vijayawada in the early weeks of 1981, he had been guilty of over-training. “My body had not quite recovered from the rigours I had put it through in the winter, and I was also not mentally well prepared for the tournament,” he says.

“I felt sluggish and uncomfortable right through the course of the tournament; and I think Modi played an outstanding match in the final. I must also say that Modi at his best was a fine player with an all-round game and no obvious weaknesses, except perhaps stamina. That loss, in January 1981, was one of the saddest moments of my badminton career.”

However, Prakash took back some lessons from that Vijayawada defeat. “It is true that, if you don’t lose, you will never learn,” he says. “All great athletes have said that they have learnt from every defeat. I went back to Denmark, and tried to analyse what had gone wrong with me. I hired Svend Karlsson, a physical trainer; and thought of how I should not repeat the mistakes I had made. Within two months of that Vijayawada loss, I reached the final of the All-England for a second time.”

Not many of Prakash’s supporters and admirers realised that he had gone into the 1981 All-England with a knee injury that had prevented him from practising regularly for some time.

“We had played a series of badminton Test matches in England, and I got injured during the second match,” he says. “I had to withdraw from the rest of the series, fly back to Copenhagen, and take complete rest for about three weeks. So I was physically not at my best at the 1981 All-England. I was tired. There was also the mental trauma that my streak of nine Indian National singles titles had been broken by Modi a few weeks earlier.

“Actually, when I went back to Copenhagen from England, I met Svend (Karlsson); and he turned things around for me. He diagnosed that I was over-training, and prescribed a different regimen of training and rest. I think it was because of him that I could play that All-England at all, and at least reach the final.”

Prakash actually overturned a 0-9 deficit in the first game against his victim of the previous year’s final, Liem Swie King; and won 15 points on the trot to bag the opening game at 15-9. But the effort squeezed him out, and Swie King, under instructions from his courtside coaches, prolonged the rallies and ran out an easy 15-5, 15-6 winner in the next two games.

All through his career, Prakash had to perforce rely on a half-smash to finish off a rally, because he did not have a big bazooka like Swie King or Chinese hitter Chen Chang Jie. A powerful smash nets its hitter several cheap points during a match; Prakash had to work harder for every point because he lacked a finish.

Nevertheless, big hitters like Chen Chang Jie rarely troubled the Indian ace. “Chang Jie was as good as anybody else,” says Prakash. “He had speed and power, but not the finer nuances of the game. Just a powerful smash can be muffled and handled.

“It was the same with Li Yongbo, who played very good singles before he became a full-time doubles player. If you could handle his smash, he did not have too much to worry you. Jens-Peter Nierhoff also had a huge smash from both flanks. But again, only raw speed and power could be tamed. If I managed to get a good length on my toss, I was confident of being able to return most smashes.”

Denmark’s Morten Frost, who was to become a close friend and training partner during the early-1980s that Prakash spent living in Copenhagen, was as strong an adversary as Indonesian Swie King.

Watching a match between Prakash and Frost was an education in itself. It was said of Frost that his footwork was like ballet; he was never seen to put a foot wrong, even against a master of deception like Prakash. The two were very evenly matched, but Frost had the edge in firepower, an attribute that Prakash sorely lacked.

The 1980 decision to train and play as a professional in Denmark may have been a good one at the time, because Prakash lacked adequate opposition in India. But in hindsight, one realises that it allowed Frost the ideal opportunity to study the Indian’s game and analyse it from every angle. Regular practice with Frost blunted Prakash’s master weapon – his deception.

And so it was that during the latter part of his career, especially after 1982, Prakash lost to Frost much more frequently than he beat him. The tall, slim Dane also had a three-year age advantage over the Indian, who burnt out a little faster because of the huge burden that leading a weak team like India in the Thomas Cup placed on him.

“I would say that Swie King was my toughest opponent, especially in the early part of my career,” says Prakash. “In the latter half of my career, Morten became a nemesis player, because he got the opportunity to study my game thoroughly and unravel all my tricks and strokes.”

The point is, Frost could concentrate all his energies on singles; Prakash had to play doubles as well, to keep in touch with this event when he was on India duty in the Thomas Cup and Asian Games team events.

That he was an excellent doubles player is well known; he has five national men’s doubles titles to his credit. Prakash could play equally well with different partners like Leroy D’Sa (with whom he won in 1973, ’76 and ’77), Kiran Kaushik (1979) and Vinod Kumar (1988), to name just three. In the Thomas Cup, he made a formidable combination with Uday Pawar.

What sets Prakash apart from several other badminton greats that India has produced is the fact that he has given back to the game every bit as much as he got from it. Had it not been for his initiative, Bangalore today would not be the proud possessor of one of the best badminton complexes in the country and an academy that has been regularly churning out quality players to try and don his mantle. The Prakash Padukone Badminton Academy (PPBA), housed in the spacious complex of the Dravid Padukone Centre of Excellence, has just completed 25 years of existence.

There could be a strong reason why Prakash, still a stickler for physical fitness, moved away from actually playing badminton with his wards at the PPBA. His lieutenant, Vimal Kumar, recounts an incident, some 15 years ago, when Sanave Thomas and Rupesh Kumar, who by that time had already won the National doubles title twice (they were to end up with eight national doubles crowns), were taken on in a friendly match by Prakash and V Diju, who was to win four mixed doubles national titles with Jwala Gutta.

“Diju and Prakash – who was then just under 50 years old – beat Sanave and Rupesh in straight games,” says Vimal. “Perhaps realising that such a beating could seriously de-motivate the national doubles champions, and prove harmful to India’s chances in the Thomas Cup and other international events, Prakash just stopped playing against them.”

Prakash does not deny that this event took place, but says with typical modesty, “That was only in a practice game; Sanave and Rupesh would have been a different proposition in an actual match!”

The fact remains that India’s most accomplished badminton player has, for fitness reasons over the past decade or so, preferred to chase a small black ball around the court than a white shuttlecock. And, watching his nimble movements at the age of 64 in the close confines of the squash court, no one has the guts to tell him that he is labouring with the wrong racket!

Source: FirstPost